December 2, 2025

Towards General Agent with Compositional Cognitive Abilities

By The CocoaBench Team

What's missing for benchmarking general agents

In the last two years, benchmarks for LLM-based agents have proliferated. We now have standardized suites for repository-level debugging, web browsing, deep research. At first sight, this looks like straightforward progress: tasks become more realistic, reported scores increase, and new agent frameworks are released at a rapid pace.

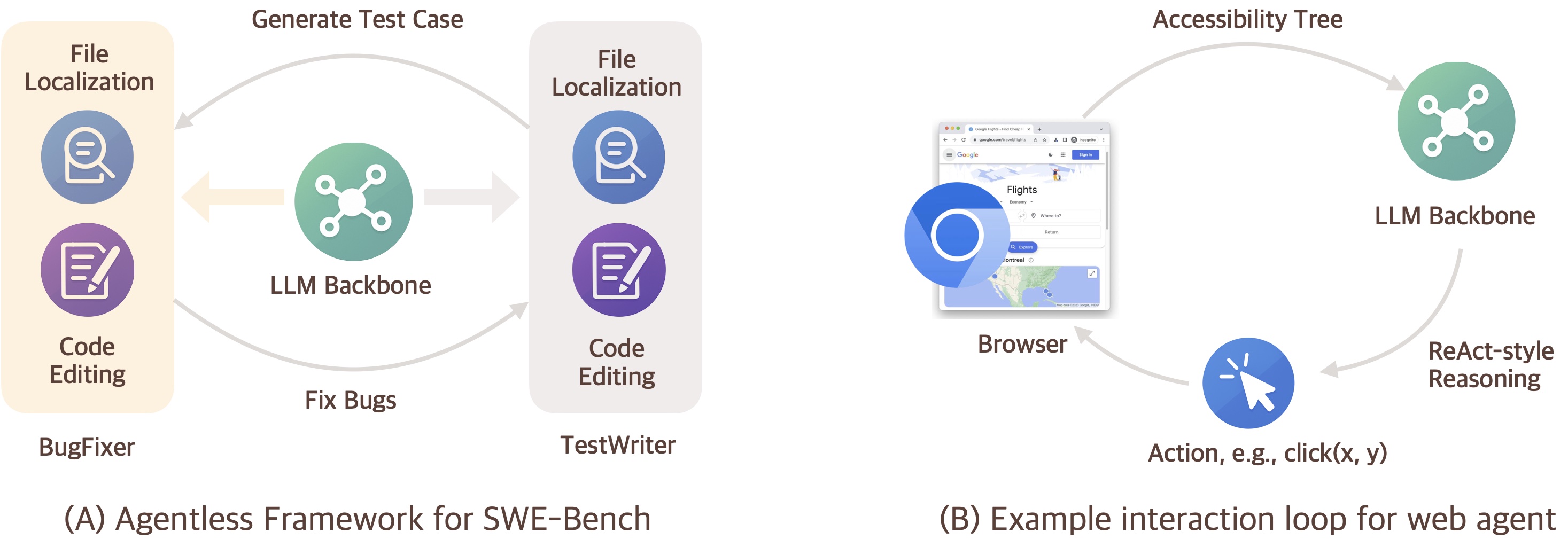

However, a closer look at how these systems are built reveals a different pattern. For example, when we look at the leaderboard of SWE-Bench, strong performance is not necessarily produced by agents that autonomously decide how to solve a task, but by agentless frameworks, predefined workflows or domain-specific pipelines that merely call an LLM at designated steps (Figure 1, left). In these systems, the framework designer specifies the overall plan, and the model is only responsible for filling in local decisions within each stage.

Even frameworks that appear more flexible often impose a strong prior on the agent's behavior. A common pattern is to define a fixed interaction loop with the environment: at every step, the latest observation is inserted into a prompt template, the model is asked to produce a short reasoning chain, and then an action is decoded and executed (Figure 1, right). This loop is applied uniformly throughout a trajectory, regardless of the task phase, the agent's uncertainty, or the difficulty of the current subproblem. The agent may choose what to click or edit, but it does not choose how to structure its own interaction with the environment.

The hidden cost of static, single-domain design

The issue is not that static systems are "cheating", nor that their results are useless. The issue is that a benchmark solved by a static, domain-specific workflow provides only limited evidence about the capabilities of general agents. When a benchmark is tightly coupled to a particular environment, it becomes natural, and often optimal, to engineer a workflow for that domain.

This is good engineering, but it primarily rewards overfitting to one environment, rather than developing agents that can easily adapt to new tasks. As a result, a system that performs well under a carefully crafted pipeline may degrade sharply under even modest distribution shifts: a different build system, a different code host, or a task that suddenly requires reading PDFs and spreadsheets in addition to text. In effect, we risk building "this-repository agents" and "that-website agents" rather than agents that generalize across domains.

Agents are becoming more general; benchmarks remain narrow

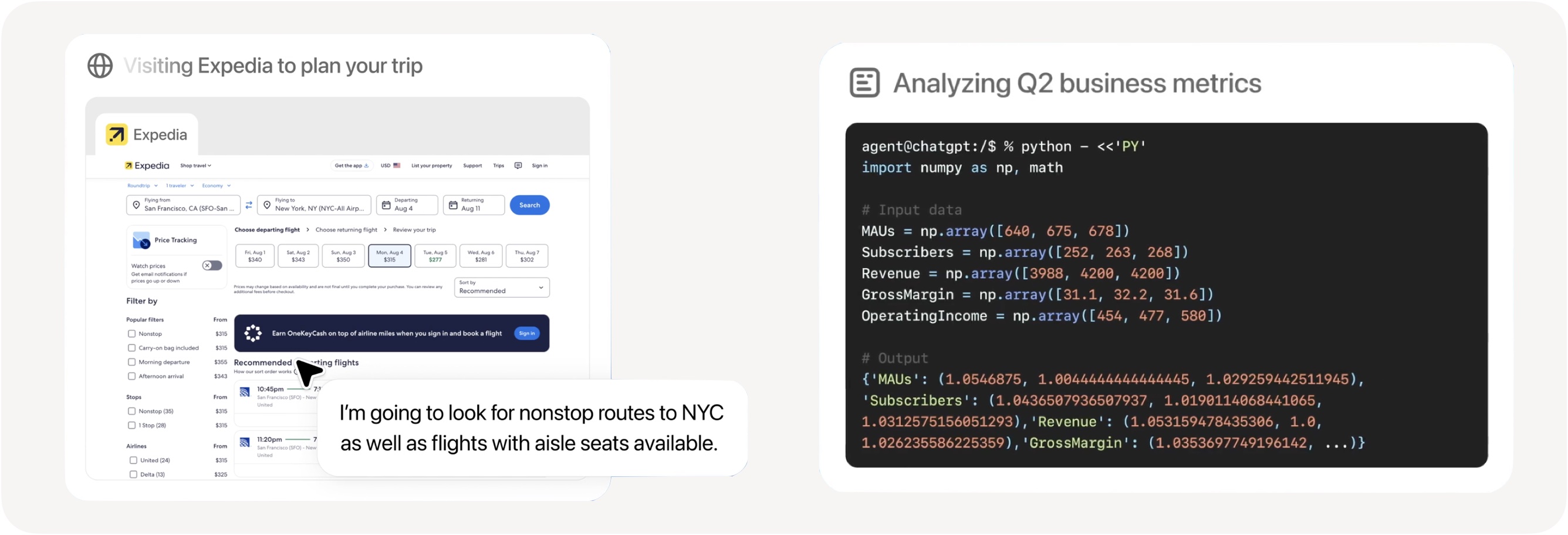

In parallel, we are beginning to see early research prototypes that move toward more general agent frameworks. Recent systems, such as ChatGPT agent and UI-TARS-2, aim to:

- operate over several general tools (browsers, file systems, terminals, code interpreters),

- act within rich user interfaces rather than text-only environments, and

- tackle open-ended, long-horizon tasks that do not fit a single-domain template.

These efforts target the objective we ultimately care about: agents that can adapt across domains, compose skills, and regulate their own behavior. Yet their evaluation remains largely anchored to narrow, domain-specific benchmarks. We currently lack benchmarks that are designed from the ground up to measure the progress of general agent.

From agents for domains to agents with flexible cognitive abilities

Recent work on agent benchmarks has started to move beyond single-domain tasks by wiring LLMs to large tool suites, e.g., TOOLATHLON, MCPMark curate extensive MCP-compatible tool ecosystems for models to operate on.

In this work, we take a different perspective. The specific tools an LLM interacts with, and communication protocols like MCP, are likely to evolve rapidly. In contrast, the cognitive abilities required to solve problems are far more stable. Humans succeed in unfamiliar environments not because they have memorized every interface, but because they apply general principles of perception, reasoning, and memory to understand and navigate new tasks.

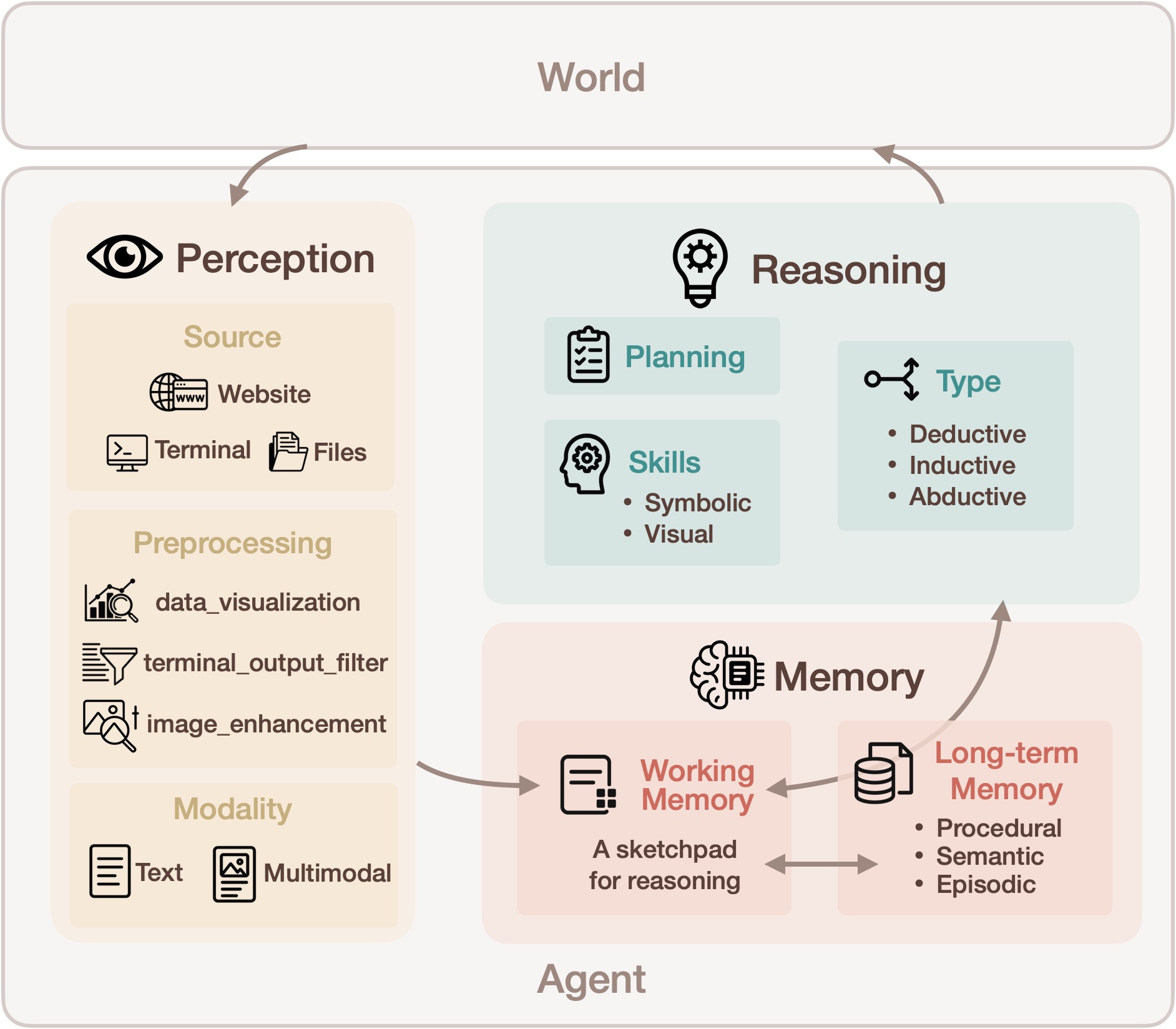

Our design philosophy therefore shifts the target from "agents that support as many tools as possible" to agents with flexible cognitive abilities that can, in principle, adapt to new tools and environments, and solve very complex tasks. We highlight tasks around three core capacities an agent should bring to any environment:

- how it perceives the world

- how it reasons and makes decisions

- how it operates memory

and, more importantly, how the agent can compose these abilities to solve more complex problems, including the metacognitive control needed to decide when and how to deploy perception, reasoning, and memory to for problem solving.

Perception

We define perception as the process of mapping the external environment into the agent's internal state, i.e., the input within the model's context window, either as text, audio, images or video clips.

Source

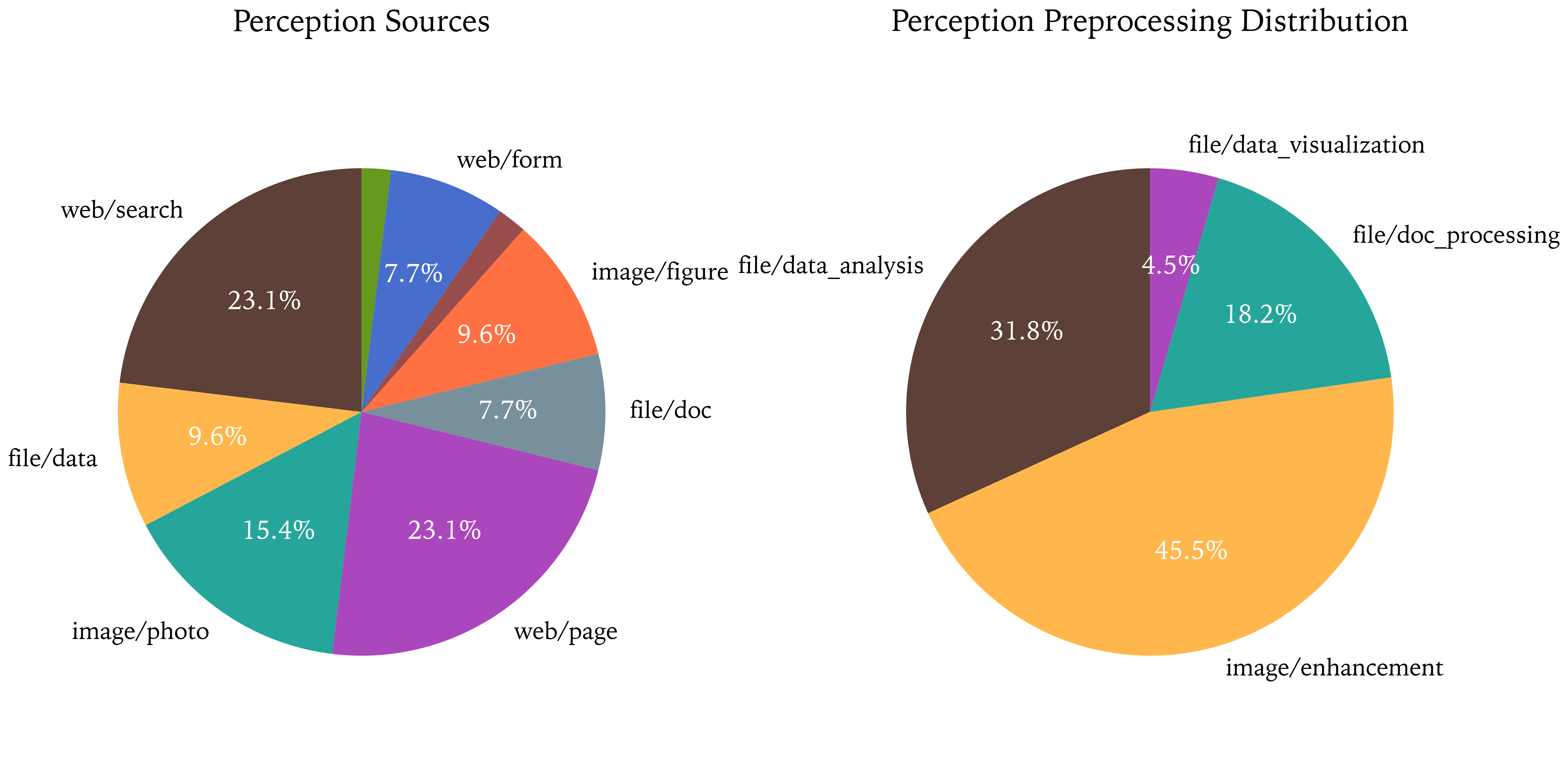

The agent may need to perceive information from diverse sources: websites, data files, images, code execution outputs, etc. For each task, we label the perception source.

Preprocessing

Perception is not simply "dump all observations into the prompt." Before committing information into the LLM, the agent may preprocess its observations. For example:

- filtering output with

grepafter a terminal command - zooming into an image region to inspect details

These operations correspond to cognitive offloading: delegating parts of the perceptual pipeline to external tools. We catalog common preprocessing strategies and annotate each task with the relevant ones.

Modality

Ideally the model should possess the ability to perceive with multimodality. In CocoaBench, we design our tasks to cover both text and image inputs.

It is important to note that there are often multiple valid perceptual pathways for completing a task. An effective agent should decide which source of information to read from, how to preprocess or transform it, and even which modality to rely on (e.g., plotting a figure and inspecting it would be more effective than processing raw numbers in the "Linear regimes" task). These choices reflect a form of metacognitive control, where the agent reasons about how it should perceive before reasoning about what to do.

Memory

Following the CoALA framework for language agents, we view memory as a modular hierarchy: a short-term working memory, and several long-term memories—episodic (experience), semantic (knowledge), and procedural (skills and routines).

In this work, we focus on working memory and procedural memory, which are most directly exposed in our tasks, and effectively managing them remains open research questions:

Working memory

Working memory is whatever the agent actively maintains in its current internal state for the next decision. Because context windows are finite, the agent must decide:

- what to keep verbatim (e.g., the most recent stack trace),

- what to compress or summarize (e.g., a long config file or multi-page paper), and

- what to forget entirely, or delegate to long-term memory.

Blindly appending everything, as many current frameworks do, quickly leads to noisy context and brittle behavior. A good framework makes these operations explicit (e.g., insert, summarize, forget) and lets the agent control them.

In our benchmark, many tasks require long interaction trajectories, so naive "log everything" strategies fail: the agent must learn to actively curate its working memory to stay focused on what matters for the next few actions.

Procedural memory

Procedural memory stores knowledge of how to do things, allows the agent to perform tasks without repetitively exploring in the environment. Examples include crafting items in Minecraft (Voyager), commonly reused routines in web browsing (Agent Workflow Memory), or specific expertise that can be used in general AI assistant (Claude Agent Skills).

In most current systems, these routines live as Python code in the framework, not as writable agent memory. We, instead, are interested in agents that can acquire, store, and invoke procedures themselves. For example, once the agent discovers an effective way to "get the highest validation accuracy of a W&B run," it should be able to reuse that same routine to inspect every run, rather than re-exploring the space of actions from scratch each time.

In our benchmark, we explicitly label the procedural skills that are helpful for each task, so we can analyze whether agents are genuinely learning and reusing these routines.

Reasoning

Planning

These tasks cannot be solved by a few actions: the agent must decide on a multi-step plan based on the tools it can use and its own capabilities. For all the tasks, we provide a reference plan that describes one reasonable solution path.

Logical inference type

For each task, we mark the dominant logical inference type: deductive, inductive, or abductive. Existing benchmarks typically concentrate on one direction (e.g., abductive reasoning in BrowseComp, where the agent must infer a hidden target from partial clues). In contrast, CocoaBench deliberately spans all three, resulting in a more diverse set of reasoning questions.

- Deductive reasoning: from general rules to specific conclusions. For example, in the "W&B logs" example task, the agent is given specific rules and raw logs, and expected to reach a specific conclusion.

- Inductive reasoning: from multiple examples to a general pattern. For example, in the "Linear regimes" example task, the agent is given raw data and expected to fit a function to the data.

- Abductive reasoning: from observed outcomes to the most plausible explanation or hypothesis. For example, to solve the "8-puzzle game" example task, the agent needs to infer the target state based on interaction with the interface.

Typically, tasks are mixed with all different reasoning directions. We do not treat these categories as rigid boxes. Instead, they provide a lens for analysis: for each task, we mark which directionality is most important, allowing us to ask, for example, whether agents struggle more with abductive tasks (explaining failures) than with purely deductive ones (checking constraints).

Reasoning skills

Finally, we label whether a task specifically stresses symbolic or visual reasoning:

- Symbolic reasoning: tasks that are better handled via code execution or precise manipulation of discrete structures (tables, logs, JSON, formulas, program traces, etc.).

- Visual reasoning: tasks that rely on spatial relations, layout, or GUI understanding, such as interpreting plots, comparing figures, or navigating complex interfaces.

We use simple 0/1 labels for symbolic and visual reasoning on each task, and they can overlap when both skills are required.

Evaluation

Our current benchmark (CocoaBench-0.1) includes 25 human-curated tasks. We evaluate several commercial agent systems on the benchmark. Our evaluation reveals several important findings:

- Our benchmark proves to be highly challenging: none of the systems are able to correctly complete more than 50% of the tasks.

- Among all tested agents, the OpenAI Agent remains the state-of-the-art, demonstrating the strongest capabilities in solving complex tasks with diverse cognitive abilities.

- Hallucination remains a major issue across all agents: extraneous or erroneous outputs frequently compromise correctness.

See our leaderboard and case studies on example tasks.

The CocoaAgent Framework

To enable rigorous evaluation and empower researchers to develop their own agents, we built the CocoaAgent framework. CocoaAgent provides seamless integration with AIO Sandbox, an all-in-one Docker environment. It equips agents with a full suite of tools—browser automation, terminal access, file operations, and code interpreters—enabling them to operate like human developers in realistic settings. Our framework is model-agnostic, and we provide example scripts for running agents with both open-source LLMs such as Qwen3-VL and commercial models such as GPT-5.1. To support robust evaluation at scale, CocoaAgent implements both dynamic runtime tests for verifying computational correctness and lightweight static-matching checks for deterministic answers. We are currently producing comprehensive results on CocoaBench using this framework, which will be available soon on our leaderboard.

Get Involved

We are continuously building and improving CocoaBench. CocoaBench is a community-driven benchmark, and we welcome contributions from researchers and practitioners with diverse backgrounds. If you've encountered a challenging real-world problem that pushed your limits, it might make a great benchmark task!

We've set up a streamlined task contribution protocol to guide you through creating and submitting new tasks. Contributors with 3 accepted tasks are eligible for co-authorship on the CocoaBench paper, which we plan to submit to a top-tier ML conference.

Have questions or ideas? Feel free to reach out to us or join our Discord community to propose new tasks or discuss ideas. (If the link doesn't work, try refreshing the page or manually add the server in Discord app using invite code: ZDaDhVCd)

Back to Introduction | View Leaderboard